🔮Just Call Them

Investor who paid homeless people to surveil government offices reveals how to get sources to tell you anything. PLUS: Why Warner Brothers will go to Paramount

Chris DeMuth Jr. is the founder of Rangeley Capital, an event-driven hedge fund and writes Sifting the World on Seeking Alpha and Substack.

He started his career doing unorthodox investment research for banks and hedge funds, a job that involved everything from tracking whose lights were on at government offices to filing Freedom of Information Act requests to get info on contract awards.

The Oracle spoke with Chris about the art of developing human sources, his contrarian take on the Warner Brothers Discovery deal, and the intersection of event driven investing and prediction markets.

This interview has been edited for length. All answers are his own.

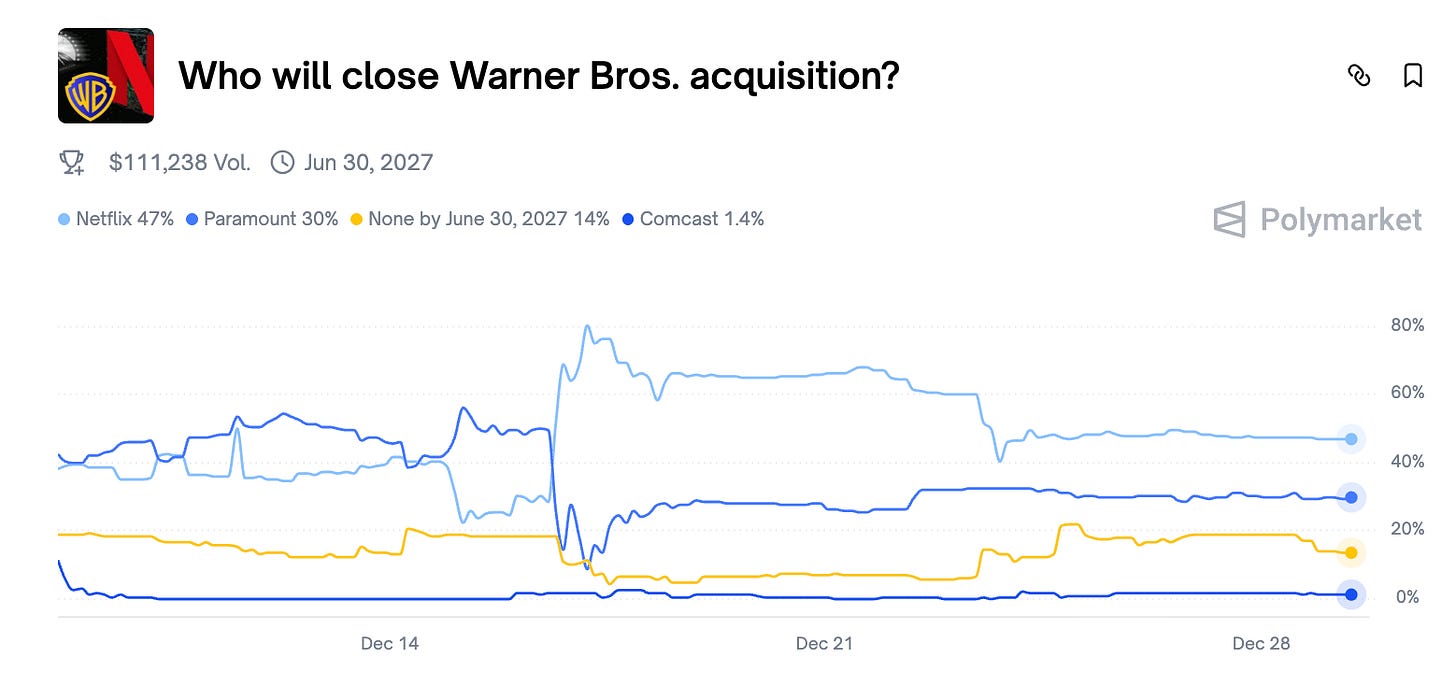

Let’s start with Warner Brothers Discovery. Netflix is leading now, but you think the ultimate buyer will be Paramount. Why?

Yes, I think those are about flipped from the likely outcome here. [note: when this interview was conducted Netflix was trading in the mid 60% range to close, and Paramount mid 30% range]

In M&A, before establishing big positions, I look for consolidating industries where there aren’t many players left and there’s more demand than supply. Warner Brothers Discovery is one of those assets. There are a number of buyers that could lead to bonanza outcomes for me as a Warner shareholder. If Apple or the Saudis determine they want to own this, they could pay me much more than I deserve.

But here’s the key: David Ellison has laid out that he thinks this content is going to be more valuable. Like with Elon’s purchase of Twitter, this involves players whose behavior and resources don’t have a lot of great comps. Larry Ellison and his family are really rich relative to conventional billionaires. The market might miss how much resource and quirky will they could bring to bear.

In my last interaction, I said that for me to want to tender to Paramount, it would need a 10% bump and a Larry Ellison personal guarantee. We got that personal guarantee today, and we did not get any disavowal of a potential bump in the next quarter, which I hope and expect in the $33 per share range.

The market seems to be placing a lot of weight on the signed Netflix deal. How ironclad is it?

I think the market massively overstates the importance of a signed definitive merger agreement. Netflix is motivated to imply a strong likelihood they will close, and you hurt your legal rights if you look like you’re not living up to your duties under the agreement. I put huge weight on things people have done and what that implies.

A superior bid that the board deems to be superior is contemplated by the agreement. They’re going to have to pay a big breakup fee, but they signed a deal without getting the best Paramount bid. It’s like an options contract. They were willing to pay a premium to buy a put. They can put Warner to Netflix at a given price and keep actively responding to other interests.

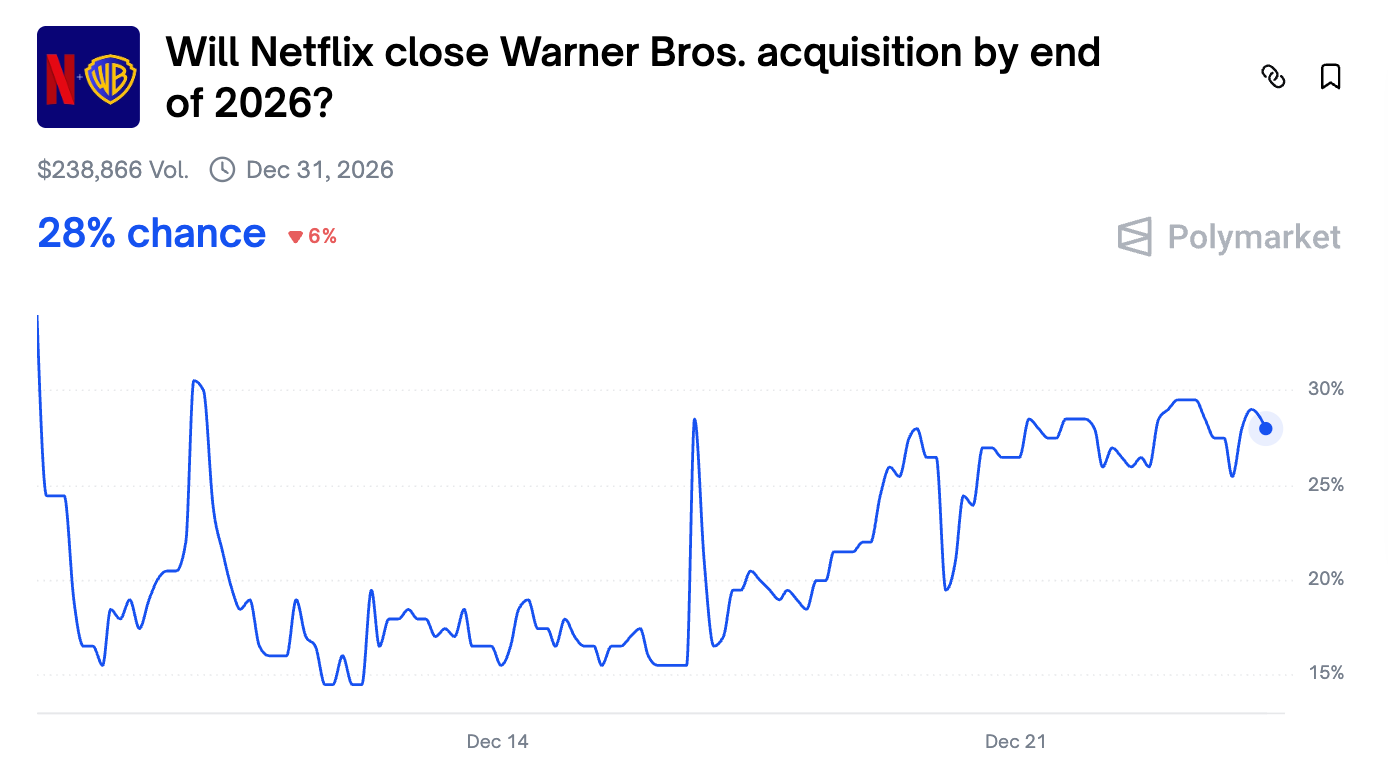

We have Netflix’s odds of closing by end of 2026 at ~28%. Why is it projected to take so long?

Tender offers tend to be a month and a half. A normal merger, three or four months. This will probably have an extended antitrust review. The idea that it takes about a year is really kind of right. So that date is not hugely influential, it’s not that different from simply “Will Netflix buy them?”

Paramount and Comcast could probably have big but surmountable antitrust reviews. Netflix could get a lawsuit or it could clear. If you look at an extended second request, about a year.

I understand that you often call people involved with these kinds of special situations and get them to tell you things. How do you do this?

Early on, Oracle was trying to buy PeopleSoft, which was trying to buy JD Edwards. The first person I called was Larry Ellison, because he was in charge of Oracle. He picked up. He didn’t have a boss. People in the middle of an org chart are always skittish that they’ll tell you something they’re not supposed to and get in trouble. So I love not just primary sources, but principals.

There are more bleeding hearts than skeptics in capitalism. More people are doing something for reasons that, in their minds, are totally righteous and pure. They’re happy to tell you if you ask.

The cost of the marginal phone call has gone to about zero. It takes five minutes. It organizes my thoughts. You just think it’d be kind of quirky and odd and fun to talk to them. And you have all these breakthroughs.

I try to get about 60 or 70% of the way there on primary documents first. Read press releases, but definitely read SEC filings. People who’ve been CEOs or CFOs of public companies say they hide all the truth right there in the SEC filings, because once you get those risks archived in Edgar, you’re safer on personal liability. Get that far first, so you’re more relevant and interesting to the principals by the time you speak with them.

Let’s go deeper. How do you even find the phone numbers of these executives?

I can quickly get contact information through private investigators and publicly known sources. We have outside services.

If I was going to try to replicate that inexpensively, without as much institutional support, I might start with email. You can just find an email format from a company. It’s often in SEC filings. Sometimes the phone number is as well.

How do you introduce yourself? What’s the value proposition for them to tell you this information?

I don’t lie and I don’t bluff. I think about the value proposition as some combination of very nice, very interesting, or very quick. If you’re a stranger asking somebody who doesn’t have an obvious reason to respond, you need to project that you’re going to be some combination of those three things.

“Nice” in a professional sense is total focus on the fact that we all have our own jobs. It’s not their job to do my job. “Interesting” is clarity that I’m going to work on this, that this is incredibly important to me. I have capital at risk. It might not be a huge dollar figure relative to somebody who manages 100 times as much, but if it’s a 5 or 10% position, I could lose several percent of my capital. It lets them know I’m going to keep asking these questions, and they might want to get their word in edgewise relative to all the other people I’m speaking with.

One of the things I often tell people is: “You do not owe me an answer to this question.” Let them be a hero if they want to be. The strategy of saying “You owe me an answer, you have to tell me” puts them in this amorphous category where they’re defending their job and their rules. It’s unpleasant with no upside.

Let’s say you get an executive at an M&A target on the phone. They can’t just tell you what bid they are going to accept. How do you actually extract information?

You get information by acting and then observing the reaction.

If I can get something 70% correct, and I’m talking to somebody who knows 100% of what I know 70% about, I have known zero people who are able to completely mask at least the binary: right track, wrong track. You’ll almost always get some kind of reaction. A smirk, a sigh, “I can’t say anything” with an innuendo that you’ll probably be happy with the conclusion. Or a more dour response if the thing you’re offering is no longer relevant because you’re going to lose.

Sometimes on the phone you’ll literally hear typing. One example: there was a conflicted telecom deal I was unhappy with. For a while I would yap at them and get ignored, clearly getting ghosted. Then one day I called and literally could hear the clicking. I started listing my demands, and it was a much more polite reaction. There were suddenly many more people in the room and it was clear they didn’t have the votes and needed mine. Their body language just changed radically. I went from being the least interesting person to the most interesting person in the world, even though I was saying the same things.

You started your career doing research for hedge funds in DC. Any stories from that era?

We would want to know whose airplane landed at Reagan National based on FAA tail numbers. We would want to know whose lights were on on a Saturday night. Some people in the government are professionally settlers, and others are litigators. So if you were under investigation for something, and on Saturday night the guy who generally settles has his lights all on, and the gal who normally sues has her lights off, that’s a very good sign for your investigation.

FOIA requests are also a great tool. For example, there are good governance rules that say you can’t contract with any company that’s corporately a felon. Well, that’s 25 out of the top 25 biggest government contractors.

So of course there needs to be a waiver process. That waiver was subject to FOIA. So I was able to get a few days’ warning on major government contracts with completely open source public information. It’s not information anybody was asking for, because you were asking for a waiver on something that hadn’t happened yet.

Another trick: different agencies, when there was a big announcement, would give people who followed closely a courtesy heads-up on press conferences. They’d tell you the binary: “Hey, don’t worry about it, you don’t need to come,” or “You do need to come.”

Once we realized they were willing to give you that, we played a game. If we had 10 people, instead of everybody asking about everything they’re interested in, each person picked a different, non-overlapping subset and then compared notes. We were able to glean a lot more information that way. We would never know if it was good news or bad news, but in terms of vectoring in on what the topic was, there were very good ways to do so.

Wait, you were out there staking out people’s offices yourself, spy-versus-spy style?

I wasn’t personally, but we had people who were, including homeless people who we would pay. It was very simple: literally whose lights were on and off. We would not break the law. We would not trespass. But we would be as proximate as we could be.

How would you go about developing sources in the Trump administration?

This is an untraditional administration. They don’t have traditional congressional relations like all past administrations. But you can get the people who are physically in DC to do some sleuthing.

You call Senate offices and talk to legislative and political assistants. I’m very comfortable getting on the phone with them. You call the chief of staff and say, “Who in your office is working on this?” I can call a state and say, “I’m an investor. I’m looking at a $5 billion project. This is going to affect 1,500 jobs in your state. It’s unclear to me if we’re going to get this approval on time.”

They always have to triage. The first thing they throw out is anything that’s not relevant to their state. So: this is how it’s going to affect your constituents. The world in which I lose a lot of money is a world in which you’re going to lose a lot of votes. What the heck is going on?

Usually a senator can figure out what’s going on when it’s relevant to their state. You can deputize them to help with research. I’ve had situations where I’ve perhaps slightly embarrassed them by not knowing something that, of course, the senator of that state should know. Either he knows, and he tells me. Or he doesn’t know, and geez, maybe he should go find out.

What markets would you like to see on Polymarket that don’t exist?

One whole category that could be plug-and-play is non-tradable merger securities. When a merger closes, you can get paid cash or stock, but you also get merger securities that are sometimes immensely valuable, but not traded anymore. These are called contingent value rights.

People like me will be looking at these for years and would either want to hedge, speculate, or benefit from the information. What’s it worth? There’s ex-SPAC guys talking all the time about what these things are worth, and nobody really knows. They’re not tradable.

A funny example: Pan American Silver Corp has a contingent value right where you had to have a spiritual consultation with local indigenous tribes in Guatemala, who don’t formally have to approve the deal, but you had to go through a process of consulting them. If you get the Guatemalan approval, you get stock in a silver company that’s up 159% this year. So you have this right sitting in a morass of trying to consult Guatemalan Indians about the spiritual aspects of the deal.

Follow Chris DeMuth Jr on X, Substack, and Seeking Alpha

Disclaimer

Nothing in The Oracle is financial, investment, legal or any other type of professional advice. All odds are time sensitive. Anything provided is for informational purposes only and is not meant to be an endorsement of any activity or market. Terms of Service on polymarket.com prohibit US persons and certain other jurisdictions from using Polymarket to trade, although data and information is viewable globally.

Thanks for the chat. I love Polymarket and am so excited that they're coming back to the US. Planning on participating at scale ASAP.

gracias polymarket excelente saludos